By Kayla Drake

In June 2022, more than 1,500 African migrants attempted to cross the Moroccan border with Spain in Melilla, an autonomous Spanish city at the tip of north Africa. In reaction, Moroccan border guards launched a military-style offensive, throwing tear gas and beating migrants with batons. Twenty-three migrants were reported dead after the chaotic frenzy, according to El Pais.

A Spanish governmental investigation later found that around 470 migrants who successfully made it into European Union territory that day were forced to return to Morocco without Spain offering asylum. This action seems to violate Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights which guarantees migrants the right not to be returned to places that threaten their lives.

Instead of reexamining militaristic border practices, the EU reached a deal — just two weeks after the clash — to pay Morocco €500 million over the next five years for immigration control. It was a seeming reward for the deadliest day on record at the Morocco-Spain border. And a contradiction with the EU’s human rights principles and its alleged quest for fair solutions.

An increasing concern with no solution

The migration of humans is nothing new. It’s been a signature feature of humanity for millennia. But as conflicts grow in unstable governments and climate change destroys people’s homes at a faster rate, migration and displacements will increase. By mid-2022 alone, more than 100 million people were forced to flee their homes, according to UNCHR.

Worldwide migration has ramifications — human rights violations, xenophobia, nationalism, extremism — that can pervert democracy and endanger lives. Yet, the European Union, a collection of some of the most affluent nations in the world, has failed to reimagine borders and immigration, and chosen instead to tighten its borders more each time a new influx of migrants approaches its democratic edges.

Some may point to Germany’s acceptance of more than 1 million refugees in 2015 as evidence that the previous statement is false. But one can also argue, that is an exception.

Despite projecting a humanitarian and welcoming image, the EU has militarized its borders by creating Frontex, a border agency. It has also increased overseas digital border surveillance through EUROSUR, and invested in externalization deals with Turkey, Libya, and Morocco to expand its reach to prevent migrant crossings. The EU’s extensive efforts to fortify its borders and prevent new migrants from entering its soil exposes an underlying belief that migrants are undeserving of security and economic gains within the EU. These techniques frame migrants as criminals and are remnants of a colonialist logic, that a country can control people outside its sovereign borders.

The very way European Union countries manage migration is to protect their host populations at all costs. Scholar Luca Mavelli says that translates into policies that prioritize saving citizen lives over migrant lives. Mavelli highlights a tension between care and security for governments, “which frames disenfranchised refugees as valuable only to the extent they can contribute to [citizens’ lives].” According to this logic, migrants’ worth is derived from how they benefit the host population — are they weak or capable, threat or labor? A source of vain morality or economic gain? These policies lead to host populations that are less sympathetic to migrants and instead view them as a security threat.

A Culture of Fear

In the EU, migrants are constructed through a lens of fear. “Fortress Europe” and the 2016 refugee crisis teach us that the current stance on migration is one of militarization. The fortress mindset is exclusionary and motivated by an immunity logic: migrants are seen as people that should be kept out so as to not “infect” the host population. But this way of governing only serves to increase anxiety among the public and perpetuate more border crises.

If we look back to after 9/11, anxious citizens in the West became more open to authoritarian measures, anti-immigration policies, and increased citizen surveillance out of fear of terrorists. Scholar Andreja Zevnik points out politicians disguised new 9/11 policies as “cures” to anxiety. An example of one such policy is when the EU created Frontex in 2004 to militarize and secure its borders.

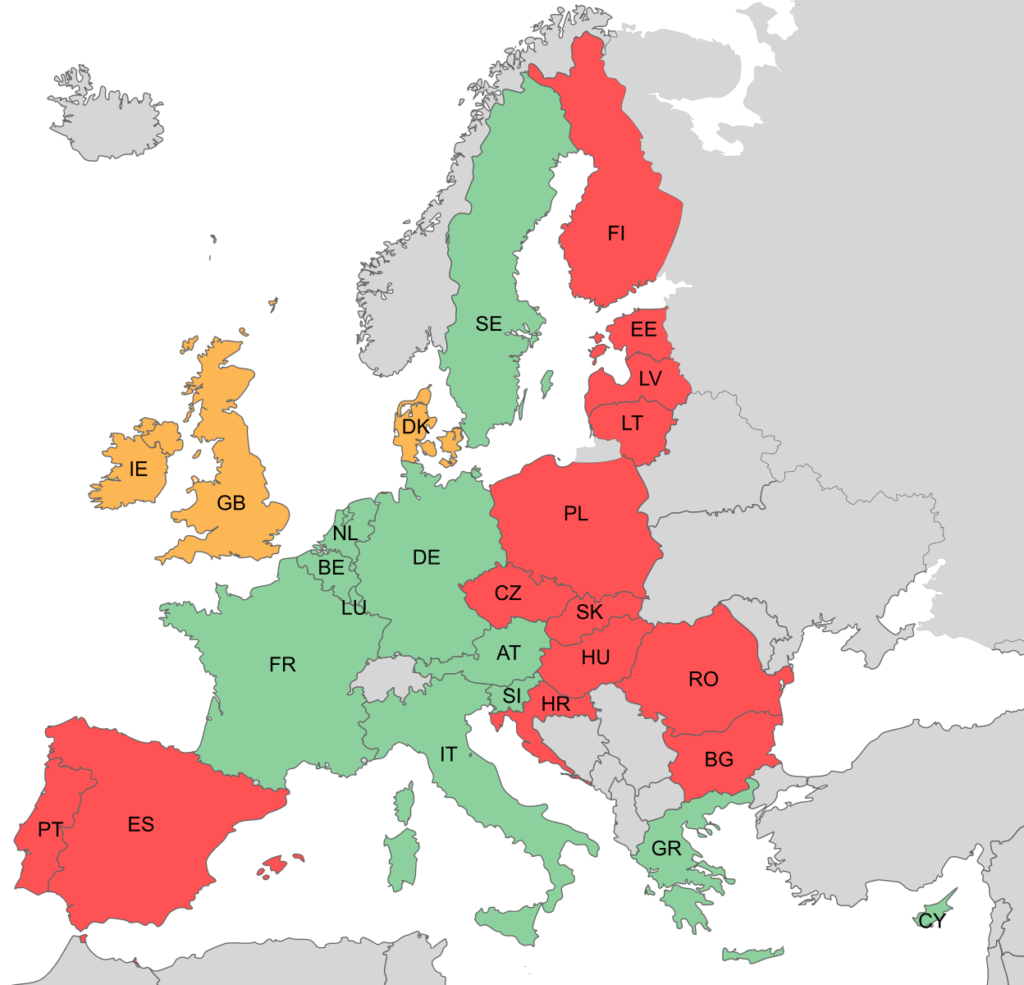

Credit: PanchoS via Wikimedia Commons

Frontex, touted by EU leaders as an answer to the increase in migrant crises, has “profoundly affected the framing and treatment of migrants” as threats, according to researcher Jori Pascal Kalkman. As an agency, Frontex lacks transparency and maintains legal immunity from any human rights violations that occur on EU borders. It is the member state who is responsible for all legal ramifications. Notably, it can authorize return flights for migrants, a process known as “pushbacks,” forcing migrants to return to places of persecution. Thus, a policy decision to attempt to inoculate a European populations from migrants has created an agency that lacks accountability and perpetuates border crises by inflicting human rights violations, rather than solving them.

The EU’s immigration system systematically relies on crisis constructions, not on humanitarianism. Each mass migration opens possibilities for further militarization. This perpetual border crisis allows for a suspension of basic human rights that democratic politicians are denying to migrants. And since emergencies and crises demand immediate action, long-term solutions are ignored, giving citizens the impression that border crises are inescapable in the modern world.

The EU’s contradictions

In 2015, 1.3 million migrants fleeing wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan trekked to the EU and sought asylum, which politicians and media outlets quickly labeled a “migrant crisis.” This moment was key. At first, the EU’s response, spearheaded by Germany’s Angela Merkel, was to rescue refugees and open borders. But policies soon shifted to denying entry.

Lesbos, Greece (which is notorious for refugee camps) has, along with Italy, involuntarily acted as a buffer zone between Europe and Turkey. Of the 1.3 million asylum seekers in 2015, nearly 40% entered through Lesbos. This geographic positioning has made Greece “the gatekeeper of the EU’s Fortress Europe response and in turn influenced Greece to harden its stance on both asylum and border control,” which scholar Anna Iasmi Vallianatou found includes the increased use of detention practices and pushbacks, often with Frontex’s assistance.

This phenomenon has instilled anti-migrant attitudes in Greek citizens. In 2016, a year after hundreds of thousands of refugees passed through Greece, 69% of local citizens felt Syrian and Iraqi refugees were a “major threat” to their country and 80% viewed Muslims negatively. This is coming from the same citizens who were nominated for the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize for their “compassion and solidarity” with refugees in 2015.

In less than a year, citizens shifted from seeing migrants through a humanitarian lens to a threat. In 2020, civilian protesters attempted to stop the EU from building a new refugee camp on Lesbos by blockading the port to prevent construction equipment from arriving, chanting “Our islands are not concentration camps”. In response, the government authorized a militarized response against their own citizens using tear gas and physical violence to end the protest and proceeded with the camp’s construction. The EU’s lack of collaboration with Lesbos residents on border security has fueled a climate of xenophobia and EU resentment.

Militarization policies and their limits

Militarization policies have also created refugee camps that serve as hotspots for human rights violations, crime, and unsanitary conditions. Refugee camps are increasingly common because of EU policies — yet international law still defines camps as a “state of exception” and an “anomaly,” according to scholar Daria Davitti. Davitti says by normalizing the state of exception, international law is used to “reproduce and legitimize violence” at borders. Once the absence of order is normalized, militarization policies can deny migrants the very asylum and protection international law is supposed to guarantee.

In Calais, France, international law has allowed the continuous eviction of a camp on the French coast nicknamed “The Jungle” where more than 6,000 migrants called home in 2016. Migrants still live in a makeshift camp in Calais today, just now without EU assistance. In fact, the EU’s response to migrants hoping to gain British asylum has been to send riot police to clear the camp every 48 hours and to make Britain build a literal wall around Calais’ port. This is a clear militarization of France’s border, actions which international law has enabled.

Migrant deaths in Spain and refugee camps in France and Greece give citizens the impression that their government cannot handle their borders. Despite militarized border methods, refugees have not stopped trying to enter the EU. This fact has kept immigration the top issue for Europeans since 2015 when heading to the polls. According to a 2021 poll from the German company Insa Consulere, 53% of citizens in ten EU countries believe it needs to do more to protect its borders.

The EU had attempted to reimagine democratic borders when it created the Schengen Area and first formed in 1993 on the basis of open borders and shared economic policies. The EU outlined policies that created “borders as meeting points rather than as barriers,” scholar Didier Bigo said. Less than 30 years later, Bigo said, the EU has moved away from its emphasis on the “free movement of persons” and returned to previous nation-state and security mindsets. Since 2014, the total amount of fences and barriers along EU borders has risen from 315 km to 2048 km. That is a sixfold increase. Citizen demands to restrict borders and build walls violate EU principles and values, and, Bigo said, limit “understanding to a ‘European only’ free movement.”

The EU’s current border security strategies demonstrate militarization methods to immunize its citizens from migrants often fail. Use-of-war methods lead to human rights violations, migrant deaths, and a lack of trust in the government. The vicious cycle prolongs and clouds concrete solutions. EU border management needs to be reimagined in a less militaristic way that returns to its core value of the free movement of persons.

Kayla Drake is a research assistant at the OCC and a Political Science master’s student at St. Louis University-Madrid. Previously, she was a journalist for St. Louis Public Radio.

To quote this article or video, please use the following reference: Kayla Drake (2023), “Why militarizing EU borders is unviable” https://crisesobservatory.es/Why-militarizing-EU-borders-is-unviable

The OCC publishes a wide range of opinions that are meant to help our readers think of International Relations. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and neither the OCC nor Saint Louis University can be held responsible for any use which may be made of the opinion of the author and/or the information contained therein.